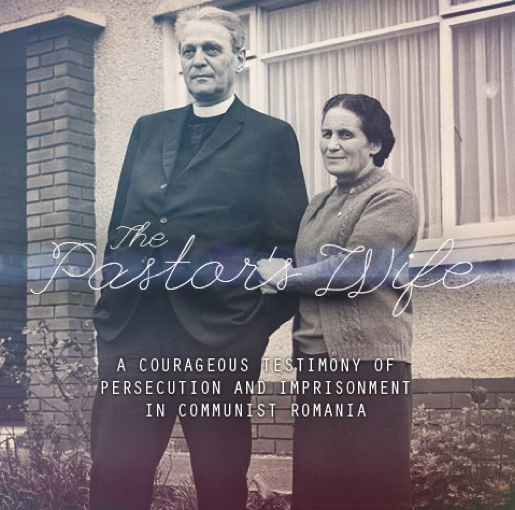

The Pastor's Wife Book & DVD Set - The Canal

IN 1951 MORE and more Communist women began appearing in the

camps and prisons. At Cernavoda I met Marioara Dragoescu, who’d been

imprisoned by the old regime as a leading revolutionary. Now she was

sent to forced labor by her comrades as a “counterrevolutionary.”

IN 1951 MORE and more Communist women began appearing in the

camps and prisons. At Cernavoda I met Marioara Dragoescu, who’d been

imprisoned by the old regime as a leading revolutionary. Now she was

sent to forced labor by her comrades as a “counterrevolutionary.”

But she would go on fighting for the Communist ideal. The Great Marxist Society was around the corner. In Mislea, the big women’s prison, she had nursed her two-month-old child—then he had been taken from her and put in a State orphanage. She didn’t know if she’d ever see him again.

She had commiserated with George Cristescu, one of the Party founders, who’d served his first prison sentence for Socialism in 1907. He’d also been the first Secretary-General of the Communist Party. Now, at seventy-two, he worked alongside us in the fields from sunrise to sunset, in snow, rain, and wind.

Sometimes I filled his barrow with earth. He had hitched himself to it like a beast. It was easier to pull than to push up the slopes. I remembered something Richard said shortly before his arrest and repeated it to him: “Under a tyranny, prison is the most honorable place to be.”

A smile lit his face. A guard shouted at him and he hurried off, yoked to his load. The next day when we were out together, I whispered, “I’m sorry to get you into trouble with my speaking.”

“No, speak! It’s like music to hear something different after so long. I’ve hungered to hear a gentle voice as I hunger for color after so much gray.”

Later he told me of his disillusion. “This communism they practice is not the ideal I fought and suffered for. I felt it would be dishonest on my part not to protest.”

Those of us who had faith realized for the first time how rich we were. The youngest Christians and the weakest had more resources to call on than the wealthiest old ladies and the most brilliant intellectuals.

People with good brains, education, wit, when deprived of their books and concerts, often seemed to dry up like indoor plants exposed to the winds. Heart and mind were empty.

Mrs. Nailescu, the professor’s wife from Cluj, said one day, “How happy you must be to be able to think and keep your mind busy and pray! I can’t. I try to remember a poem, and in comes the guard shouting. At once my mind goes back to this everlasting camp. I can’t concentrate. I can’t discipline myself.”

“Society” women were often the most pitiful. Life was harder for them than for anyone. They’d lost the most, in the material sense; and they had the fewest inner resources to fill the gap. A rubble of old games of bridge, hats, hotels, lost weekends and lovers rattled about in their heads like junk in the back seat of a car. Their nerves gave way first, as did their soft white hands.

After work, women came to religious prisoners and asked, begged even, to be told something of what we remembered from the Bible. The words gave hope, comfort, life.

We had no Bible. We ourselves hungered for it more than bread. How I wished I’d learned more of it by heart! But the passages we knew we repeated daily and at night, when we held vigils for prayer. Other Christians, like me, had deliberately committed long passages to memory, knowing that soon their turn would come for arrest. They brought riches to prison. While others quarreled and fought, we lay on our mattresses and used the Bible for prayer and meditation, and repeated its verses to ourselves through the long nights. We learned what newcomers brought and taught them what we knew. In this way an unwritten Bible circulated through all of Romania’s prisons.

This is an excerpt from the book The Pastor’s Wife. To purchase this book, please click here and to purchase the book and DVD, please click here.